A while back I wrote a blog on gender diversity in relation to the construction industry. The article was based around raising awareness of the under representation of women in general across the construction space. Aside from noting my own awareness increasing as we had started looking at our own backyard here at OneStaff, it led me to look at the generalised arguments I had encountered from within the industry over the years. In particular relation to blue collar roles, we identified and addressed a range of common excuses for the under engagement of women in industrial roles and provided some general counter arguments.

At the time of writing, I remember thinking how strange it was that women were so under represented and commented toward the end of the article that the purpose of increasing engagement of women in this space seemed a relatively straight forward decision – though it did require people to start thinking about how to engage. In today’s society, I would hope that making the effort in this space should be obvious for basic moral reasons as opposed to any form of tokenism, but even aside from my personal opinions, as the manager of a business it just represents good business practice. Cutting your available pool of prospective workers to exclude 50% of the population is insane in business terms within any economy, let alone one currently experiencing and expecting a prolonged period of skill shortages which most New Zealand industries are currently facing. Despite this, the issue of under representation still exists. Even if a company wanted to increase female engagement within their workforce, the numbers of available and suitably skilled women is still not where it needs to be.

With International Women’s Day, I have been thinking more around the engagement of women in industry, and about how we got to this point. It’s been a noted discrepancy for many years, yet not a lot appears to have been done until quite recently to address it, and potentially what could be done better to help.

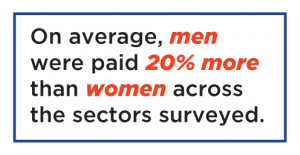

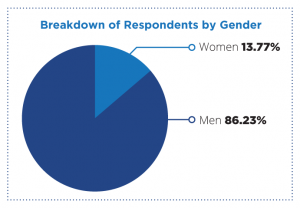

Recently, OneStaff ran the first of what we hope will be an annual wage-based survey for all blue-collar workers in New Zealand, across all levels, and across all industries. With 10,000 respondents, the core intent was to create some transparency around wage rates by industry and experience, and also to better understand some motivating factors held by workers in different demographics. We uncovered a lot of information tied to this, however, the focus from the substantial media coverage we received was predominantly based on the difference in median pay rates between males and females across each industry, which were quite telling (as was the total male to female spread in the survey respondents).

Recently, OneStaff ran the first of what we hope will be an annual wage-based survey for all blue-collar workers in New Zealand, across all levels, and across all industries. With 10,000 respondents, the core intent was to create some transparency around wage rates by industry and experience, and also to better understand some motivating factors held by workers in different demographics. We uncovered a lot of information tied to this, however, the focus from the substantial media coverage we received was predominantly based on the difference in median pay rates between males and females across each industry, which were quite telling (as was the total male to female spread in the survey respondents).

The initial reading led many to jump to the conclusion that this was an issue of pay disparity i.e. the $5 difference in median rate within the construction industry being taken as a $5 hourly rate difference between comparable skill sets and experience and applied simply on gender difference. The truth is that this actually represents a disparity of representation across all roles and experience levels in the category. The results showed quite clearly that the more experienced you are, the more you get paid, which stands to reason. The difference in median rate in this case is driven by more females being paid less due to not enough being represented within the experienced category (with the higher rates present to pull the lower median up).

The initial reading led many to jump to the conclusion that this was an issue of pay disparity i.e. the $5 difference in median rate within the construction industry being taken as a $5 hourly rate difference between comparable skill sets and experience and applied simply on gender difference. The truth is that this actually represents a disparity of representation across all roles and experience levels in the category. The results showed quite clearly that the more experienced you are, the more you get paid, which stands to reason. The difference in median rate in this case is driven by more females being paid less due to not enough being represented within the experienced category (with the higher rates present to pull the lower median up).

It’s not saying that women have no representation, just that the massive under representation is noted and it feels as if nothing much has been done to address the issue over many years. The 1940s gave us such iconic images of the J. Howard Miller “We can do it!” campaign with the woman in overalls rolling up her sleeves, flexing muscle and promoting the increased engagement of women into industrial services. That was in the 40s and built off the back of the war effort (for the Westinghouse corporation). The point is, engagement of women in industry is not new. Women have always delivered and represented in the industrial space when engaged. What has been missing is the amount and consistency of encouragement to continue to engage overtime. The effect is seen in our industries today through under representation and utilisation, resulting in limitations.

While the finding of under representation in the What’s My Rate survey was not astounding, it did make us start thinking about why and what could be done about it. Most importantly, it also provides a measurable line in the sand from which we can measure the effect of any changes that may come into play before we run the survey again later this year.

What we would like to see is the median difference start reducing year-on-year as females gather more experience and develop through the progressions that accompany a career within each industry. As the wages increase in line with these progressions, the female median should begin to rise and the difference close up. If it doesn’t, then we really need to start looking at why. There are several possible reasons change may not happen, and subsequently solutions for what can be done to avoid them.

A. Identifying Pay Disparity

If representation and progression in experience is increasing yet the median difference remains constant (or even if it increases), then we potentially have an issue with pay disparity (women being paid less for doing the same job).

To address this, we need to examine the roles we have and ensure that compensation for experience and skill is based solely on those measurables. Do we have a uniformity of outcome and expectation that guides the setting of rates? Individual differences often exist that may justify differences in remuneration – but you need to avoid assumption and ensure these differences are actually based on skill and experience, and most importantly the associated outcomes from applying these, are not discriminatory practices. If you do find differences in wage rates between people that are producing the same outcomes, then you need to examine why and address the discrepancy. The creation of an outcome matrix (what outcomes you expect a role to deliver and defining parameters for pay rates within a role type) is a good way to be objective in your measurement. Take the person out of the equation. If there is a difference in rate, but no outcome difference, then it’s quite likely there may be some sort of conscious or unconscious bias to how your wage rates are set and this needs to be identified and corrected. If the only difference identified is due to the personal characteristics of the individual rather than outcome (e.g. age, sex, race, etc.) then it’s discrimination and you need to remove it immediately by correcting the issue and standardising your policies and procedures for defining rates.

B. Identifying Bias and Engagement

If the median remains constant despite more females entering the industry, and there is no progression, then we may have an issue of bias preventing women from progressing into higher paid roles (like a glass ceiling effect). This will lead to engagement issues where the number entering may be increasing, but the median will remain constant as women are coming in at the lower end but not sticking and leaving the industry without progressing further.

Whether you’re running a team of people, or a small crew, it’s critical to have a development plan for the people within the operation. This doesn’t mean that you need a step by step pathway and timeline to them having your job, but there does need to be a development plan so that people can see where they fit into the scheme of things, and where their value sits in terms of their output. People want to know what they are working toward over the longer term and where this can lead them. In terms of engaging women into your workforce, the risk is that if people are new to a field (such as a lot of women in industry are) and they cannot see a viable future worth working toward, one that engages and accommodates them as a person, they will subsequently leave. This is true for men and women, however, in the instance of addressing any perceived gender bias in progression (ensuring it’s not just men progressing and women being held back or vice versa), having a plan in place based on measurable outcomes and based on skills as opposed to the person is a good way to be objective. It’s also critical that any development plan is realistic, and that people follow through with what has been set and outlined in a systematic way. Putting timeframes around measures like this is useful and ensures you revisit it regularly and objectively.

C. Attraction

The results from failure in this area are likely the most obvious as they will look the same or worse than current, and this will eventuate from nothing being done. If industry does nothing to further promote women engaging in industrial roles and careers, then we will never increase the representation of women in these fields.

This is one of the key areas where industry really needs to step up if they are to address the issue of under representation of women. Getting appropriate and targeted messages out that work in industry – whether construction, logistics, manufacturing, engineering or infrastructure – is a viable career path early on in the life cycle of women, is critical to attracting more people. This message needs to be engaged much earlier on than school leaving so that life and educational choices are made toward this. School talks, industry experience sessions, promoting opportunities, scholarships, direct marketing, sponsorship, building productive examples, promoting to the target audience and building work environments that are accommodating and inclusive –all of these ideas are things that industry bodies need to increase engagement in before career choices are made so that women are aware of the myriad of opportunity and career development available and can factor or work toward these when deciding how to progress with their lives.

Closing Thoughts

These are just a few ideas that occurred to me in relation to the results and in thought around the issue. However, like most issues in life there are many complications and there is very rarely a single silver bullet to correct all problems. Generally, the solution only comes from systematically identifying barriers and tearing them down as they are discovered, then re-examining to find more. Hopefully the above provides some sort of starting point, or even some basic concepts to begin looking at your own business practices.

What is certain is that a complicated issue such as this requires consistency and a commitment in purpose over a sustained period of time. There also needs to be a genuine intent and drive to want the outcome – and perhaps this is the most important factor in this type of issue as the benefits of getting it right and having better representation are both moral and logical for personal and business reasons. Tokenism, or quotas are not the answer. Genuine intent and plain integrity in processes and practice when attracting, hiring, recognising, and developing women into industry is what will see those companies that want to improve be successful in their endeavours, and be the employer of choice in their markets, which every business leader should be striving for.

If you would like a copy of the OneStaff What’s My Rate report, you can download a copy here.